CONVERSATIONS ON CONFLICT PHOTOGRAPHY

Excerpts from Lauren Walsh’s seminal book of the same title

Featuring the work by 15 award-winning photographers whose groundbreaking images have often defined global conflicts. Through these images, this show examines the stories behind the photos and the ways the photographers approached them. The exhibition is curated by Walsh and Keith Miller.

A freedom fighter, from one of the anti-government forces, enters the town of Mutoko, Rhodesia and is given a hero’s welcome as the war comes to an end, December 1979. © Alexander Joe.

The editor at the Rhodesia Herald never wanted this one published. Yet for me, this was the strongest of the pictures I had taken. But the editor said to me, “Why are you trying to spread alarm among the people?” But he didn’t mean the people; he meant the white population. This newspaper was very pro-government. [Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, was a former British colony, under white minority rule.] This was a war of rebellion, and the paper’s position was that no one wanted the rebels there. Yet here is photographic proof of a fighter being given a hero’s welcome. But that was the wrong narrative for the Rhodesia Herald. So the image never ran in the paper.

-Alexander Joe

This baby was born prematurely at twenty-seven weeks. Her twin brother died immediately after birth. The neonatal ward of the MSF hospital in Khost, Afghanistan, 2013. © Andrea Bruce/NOOR.

Working with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)/Doctors Without Borders is interesting because you come from a photojournalist background, which is supposed to be neutral in perspective, and then you move into a more advocacy-oriented arena. I go back and forth in my feelings on that. But I find MSF wonderful to work with. Their take is: these important issues aren’t getting coverage anymore. And because they’re not being covered, organizations like MSF have been hiring us journalists as journalists. MSF is completely hands-off on the actual style and angle of coverage. Their goal with this image was: We just want people to know that maternal mortality in Afghanistan is a huge issue that is not being talked about. We don’t care if you mention MSF. Just report about this issue.

Unfortunately, the reason why most magazines and newspapers often won’t run the story, if in fact they won’t, is still because of the issue itself. It’s because they don’t have the space to run the newest step in the war in Afghanistan, let alone something like maternal mortality, which is nothing new and which will depress their entire audience.

-Andrea Bruce

Afghan men walk alongside an unpaved road on the way to Bamiyan in central Afghanistan, December 2010. © Benjamin Lowy.

I was one of the first people to start posting iPhone pictures, journalistically, online. But take this photo from Afghanistan, you have to think about it from two perspectives: my point when I was shooting it then, and iPhone imagery now, what it means now. They’re two very different perspectives. When I started shooting with the iPhone, it was a new tool that meant new things. People hadn’t seen images like this before, and so that whole idea of grabbing people’s attention was that much easier. This square format, the weird border, people didn’t know what it was. Also, using this border ensured I didn’t crop anything. And I was able to post right away. I was essentially live-streaming my work.

-Benjamin Lowy

Protesters run for cover as riot police fire tear gas on the first day of the Egyptian uprising, Tahrir Square, Cairo, January 25, 2011. © Eman Helal for Al-Shorouk newspaper.

Some of the protests were dangerous. I was covering the revolution as of its first day, January 25, 2011. At first, the gathering in Tahrir Square [in Cairo] was small, but in the middle of the day, and suddenly, so many people came from different locations, everyone screaming and crowding into the square. The police were shocked because they didn’t have any policy in place for crowd control, so they were shouting, too, trying to organize people into groups to manage them. But they didn’t know how to get control. There were big clashes, and police used tear gas. I stayed until around 9:00 p.m. that first night.

Over the following days, the government cut all cellular and data service—no cell phones, no internet. So I didn’t have the ability to contact my newspaper or send in pictures; I had to bring everything in myself. Because the clashes were dangerous, the newspaper announced that female reporters had the option of staying home over the next few days. A few of us decided to keep working.

-Eman Helal

The Syrian Arab Army has used chemical shells on the frontlines in Jobar, Syria. A rebel fighter receives eye drops after exposure to the chemical sarin, April 16, 2013. © Laurent Van der Stockt.

As a journalist, you have to be 100% sure

of what you're documenting.

As a journalist, of course, you have to be 100 percent sure of what you’re documenting. You have to be suspicious yourself, looking for any cracks or gaps in the evidence. So we stayed two months on this; we had to be there and working to figure out the truth of this story.

Once we had the evidence that the government was using chemical weapons in its attacks, we had to have it recognized. In the end, the French government lab returned a positive analysis.

This is one of the few times, I’ve been told, that journalism really moved diplomacy on such an international scale. The French government announces the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime. Then Britain announces it. So the United States and Obama have to do the same. As a result, the US helps arm the rebels. And there was an attempt at political solutions, with Syria eventually claiming it would hand over chemicals to Russia and the US.

But then, in the end, it didn’t change anything. And look, chemical weapons were used again some months later, and still after that. Remember the attacks of 2017 and 2018?

-LAURENT VANDER STOCKT

Child miners look for gold deep in the rebel-controlled area of Bavi, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2013. The gold is then smuggled to Uganda and sold to the Ugandan military in exchange for weapons. At the time, the UN considered the warlord in charge there, Cobra Matata, a “gun-for-hire” who allegedly worked in collusion with the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo to keep control of the mines, to protect the illegal earnings of the Congolese soldiers. © Marcus Bleasdale.

Because I have an economics background, I always gravitate toward the financial side of conflicts. War doesn’t exist in a vacuum. You need financing. So where is that money coming from? I documented the diamond mines in Sierra Leone, which were controlled by the RUF [Revolutionary United Front], because the diamonds were financing the conflict.

That work then took me to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where I continued looking at how natural resource extraction is interwoven with conflict. I documented brutal mining conditions, overseen by both rebel and government militias, vying for power and money. Sometimes children are forced to work, excavating minerals like tungsten, tin, and gold, which get used in computer electronics that are omnipresent in the West. Think: laptops, cell phones.

First, I try to look for reasons why war exists and then I explore the impact it has on the population. Then, I try to explain, through photography, the financials of it. There have been statistics, about the Democratic Republic of Congo, that cite approximately 5.5 million people who have died as a result of the war, most of them from lack of access to adequate healthcare and medication. The pursuit of profit, in this case through the abusive control of illegal mines, is driving these dangerous conditions.

-MARCUS BLEASDALE

“I joined the YPJ about seven months ago, because I was looking for something meaningful in my life,” says Torin Khairegi, eighteen, at Zinar base. “When I am at the frontline, the thought of all the cruelty and injustice against women enrages me so much that I become extra powerful in combat. I injured an ISIS jihadi in Kobane. When he was wounded, all his friends left him behind and ran away. Later I went there and buried his body. I now feel that I am very powerful and can defend my home, my friends, my country, and myself. Many of us have been martyred and I see no path other than the continuation of their path.” Semalka border, Rojava, Syria, 2015. © Newsha Tavakolian/ Magnum Photos.

I went to Syria in 2015 to take pictures of Kurdish women fighters who were combating ISIS in the northern part of the country. At the time, there had been talk about these women who were such heroes because they were fighting a devil. So I went in influenced by that mindset, thinking I’d be documenting a story about unimaginably powerful, brave women, who believe in what they’re doing. When I got there, it was more complicated.

These women, part of the YPJ, a defense unit of women soldiers, go to the frontlines, come back for a few hours of rest, and then leave again to the frontlines. That may seem straightforward, but in fact there is a huge “gray zone” with how to understand their lives and experiences. I speak their language because I’m half Kurdish, although the dialect is a little different and so the women didn’t realize I could understand all they were saying. So in front of me, they’d be asking of their commander: “Am I saying the right things?” I realized they were scared of saying the “wrong” thing, because they felt a need to be seen in a certain light.

-NEWSHA TAVAKOLIAN

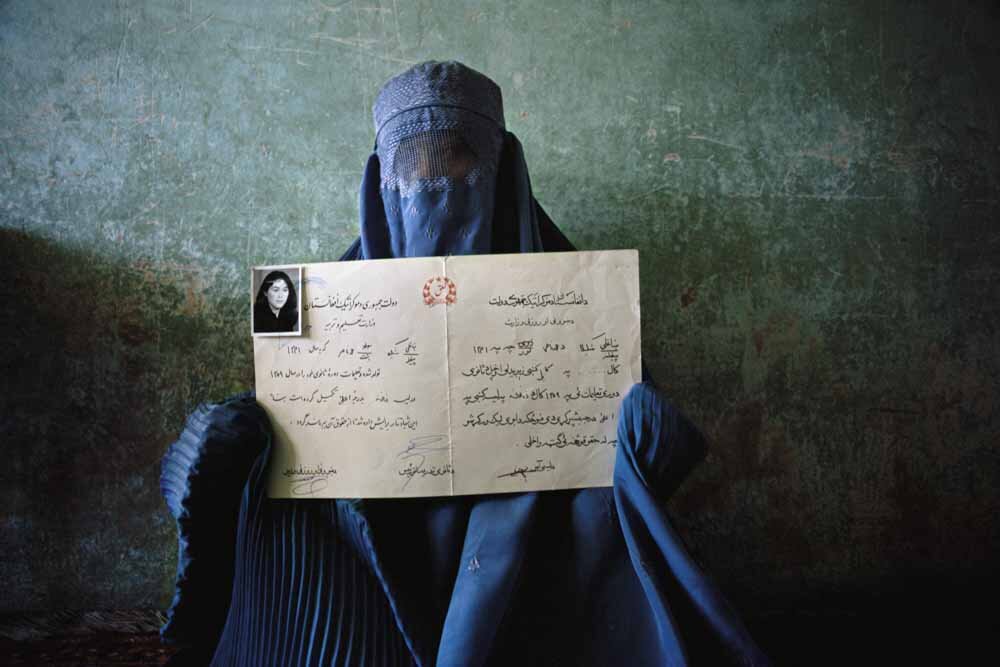

An Afghan woman wearing a burka displays her business school degree, which she received prior to the Taliban taking power. Under the Taliban, she was forbidden to work or study. Afghanistan, 1998. © Nina Berman/NOOR.

This woman told me that she had wanted to continue her studies, but wasn’t able to. She had once graduated with a small business degree, so I asked her where the certificate was and she told me it was at her home. We went there, and she pulled it out. I had no idea that her picture was going to be on this degree certificate, but there it is on the upper left. And for me, that makes this photo; it completes the picture. The “faceless” woman who isn’t allowed to complete her studies does have a face and an identity.

-NINA BERMAN

Young girls leaving an internally displaced persons camp in Darfur to gather firewood for their families. For some, the work will take over a day and lead them beyond government checkpoints, which then exposes them to rape or other violent attacks. June 2005. © Ron Haviv/VII for UNICEF.

This is a highly aesthetic photo that doesn’t play into the usual American perceptions of disheveled displaced persons. You’ll have a connection to this girl through the aesthetics, through the beauty of what’s going on, and you will want to know more, which can only come across with a caption. When you find out what she’s doing and who she is, you’ve already built up a relationship with her, and then you think, “Oh my God, this poor girl. She’s about to walk with her two friends to look for firewood, where obviously there’s no firewood. These girls could get killed, but their families need firewood. She’s a displaced person. She’s in Darfur, in the middle of a genocide,” and so on. There are times when the caption is imperative. But I’ll use aesthetics to pull you in.

I took this shot with a host of aesthetic concerns in mind. There’s her body language; she’s resilient and strong. I made the conscious decision to photograph her as I saw her strike a heroic stance. Simultaneously, the horizon line was very important to me, so there was also an aesthetic reason to crouch down for the shot. It would be a very different picture if I were of equal height to her; and most certainly, if I was looking down at her, from a taller position. It’s all about creating an emotional connection with the viewer.

-RON HAVIV

The bullet-ridden body of a man allegedly killed by the RAB was found in a pristine paddy field, which the RAB claimed was the site of a gunfight. This photo, a re-creation of that scene, is from the Crossfire series. © Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World.

The Rapid Action Battalion [RAB] is an official anti-crime force that carries out extrajudicial killings in Bangladesh, and my Crossfire photo show, which is about those killings, was closed down by the government.

So we took the government to court and they had to back down. Eventually, we had the show for one day. There were riot police around the show. The exhibition had taken on a life of its own and in my reckoning that is the most powerful, most effective exhibition I’ve ever had. It actually made a difference in Bangladesh. That show, at the time, brought down the frequency of extrajudicial killings quite dramatically.

At the show, we had in-depth interviews and case studies on the murders that were carried out by the RAB. We put all of that on an interactive Google Earth map, which was available in the gallery. People had to use these resources to figure out why this picture was important. There was no caption with the photo. It was simply denoted as “a paddy field.” So what did it mean? Okay, you look at it, it’s a pleasing image. But once you begin to put it together, the picture takes on more sinister tones.

It’s when you find the case study pegged to this image that you begin to recognize the story as it was presented by the Rapid Action Battalion. Their version: a person was caught in an ambush (a crossfire) and he died. But if there is a skirmish in a paddy field, the paddy field gets damaged, right? So why, except for where the body lay, was the paddy field found to be pristine? Then you learn that the person had one bullet hole in his shirt, but three bullet holes in his body. And slowly you begin to unravel things about the underlying aspect of that photograph. The logical conclusion—that the victim was killed elsewhere but the body dumped there, in the field—was pretty obvious.

-SHAHIDUL ALAM

An Afghan man injured in fighting is helped as violence escalates for migrants waiting to be processed at the increasingly overwhelmed Moria Camp on the island of Lesbos in Greece, October 22, 2015. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

Often, my relationship to the subjects I photograph is fleeting. I feel a tremendous empathy for many of these people. But let’s be frank, I have a passport in my back pocket, an American passport. And at the end of many days, I get to go back to a hotel while they stay in some condition of suffering. That doesn’t mean I don’t try to understand what they’re going through. But I would never claim to fully understand. That would be insulting. But I’m there, and that matters.

Frequently in these situations, the subjects and I don’t speak the same language, as was the case with this photo. But I made sure that they understood who I was. I’m a professional. I’m not here on a personal trip. I’m trying to share their situation with the world. I will use my eyes or body language or actual language to communicate. You have to pay attention to their body language, too. You try to get a tacit consent. This happens again and again. You show up someplace and the people understand what outsider journalists represent. We can get the stories out.

-SPENCER PLATT

Population of San Isidro with Sandinistas after the surrender of local National Guard, Nicaragua, June 13, 1979. © Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos.

The importance of an everyday moment

shifted and so did the visualization of it.

My concept of the importance of an everyday moment shifted and so did my visualization of it. The everyday became more about the mundane as connected to the larger conflict. There’s an example in my Nicaragua book of an “ordinary” moment—a young woman in the street pouring a cup of coffee for a young guerrilla. Many people have said, “Gee, that’s such an odd photograph.” For the most part people are expecting the “bang bang” of engagement. But I could only see that mundane moment as significant, because I was trying to portray the relationship between the civilian population and the militants. In a sense, it captures the average-ness of everyday life; but amidst an unfolding insurrection, it felt heightened. It was the “everyday” now translated to the setting of a collective insurrectional process.

As the conflict evolved, I wondered, “Where are people if they’re not in the streets? Are they going across borders to be in refugee camps?” No, they were staying and providing meals. I was looking for moments that communicated relationships. In the end, this one is very expressive of the interactions that characterized that particular time in the popular struggle in Nicaragua. People didn’t run away. They stayed. They supported.

-SUSAN MEISELAS

I just didn't know if breathing in those fumes was safe.

I was wearing PPE and I used alcohol to wipe down my camera gear. For this photo I am dressed just as those figures are. The only difference is that they’re carrying sanitization equipment and I am carrying camera gear.

It was difficult to take this picture, or rather, I was nervous because I just didn’t know if breathing in those fumes was safe.

-ALY SONG

The photo becomes something more than that specific moment;

it’s something essential about this greater moment in history.

One particular thing I wanted to experience and photograph was the 7:00 PM clap because it was such a unique thing. You look at this photo and there is something about that shield, something almost angelic. I felt this when I saw that moment.

When you can’t see faces, you have to look at the moment another way. Often you want to capture someone’s eyes; they’re expressive. Here, I couldn’t do that, but I think the gesture itself is revealing. Is she holding her hands up for help, or praying? In actuality, she is clapping but I caught her frozen before her hands meet. So then the photo becomes something more than that specific moment; it’s something essential about this greater moment in history.

-NINA BERMAN

This photo is more than a father-son portrait.

The two are reading a book they picked together from the free library in George Floyd Square. It might be a moment you would otherwise pass by, but this is an image that challenges the usual perceptions of Black men, particularly in this space that memorializes the violent death of a Black man. This is a tender, quiet interaction, and I hope it deepens the context and invites new perspectives on the Black Lives Matter movement.

-PATIENCE ZALANGA

For the journalists here, it was easy to see that the

government’s numbers were false.

You know, the authorities weren’t telling the public how bad the situation is, that the hospitals are completely overburdened. Officials tried to hide that as much as possible when it was really bad here.

I don’t know official numbers, but organizations said the death rate this year was almost double what the government was reporting. But I think that was happening all around the world. For the journalists here, it was easy to see that the government’s numbers were false. For example, they announce “100 people died yesterday” and I know the true number is higher because I’m with the private workers, who are collecting the dead, and we see thirty deaths in just one sector of Lima, while people are dying all over the city and the country, and communities in the jungle were getting hit really hard just then. So the number had to be higher than the 100 the government was reporting. Maybe it was a strategy of the government to keep people from being alarmed.