IMAGE FOR CONCEPT

INDIRECT REPRESENTATION IN PHOTOGRAPHY

OCTOBER 15 - december 4, 2019

LECTURE & RECEPTION NOVEMBER 21 AT 5PM

Recognizing the place and potential for alternative processes and image making in an academic exhibition environment

Photography, like no other medium, is intrinsically tied to the technology used to produce it. Beginning with the most primitive attempts at recording projections through a camera obscura, image makers through history have pushed photographic technology through each iteration of its evolution. Early processes such as daguerreotypes, tintypes, albumin, and cyanotypes were quickly refined and polished in the pursuit of cleaner, clearer, and more accessible imagery; as was the camera machine itself.

In the roughly 200 years since the first working prototype of a machine that could capture a fixed image the camera apparatus has matured in ways that none could have predicted during the early days of its inception, and whose latest iterations still manage to astound and surprise. Alongside the technology, the role of user has progressed in a similar manner. From operator, to technician, to photographer, to artist, the user in this history has been both object and subject, innovator and servant.

Recognizing photography and the role of the photographer in an academic environment requires an examination of this non-linear, experiment-based, results oriented process and the people who pursue it. Image For Concept brings together the work of four image makers utilizing the photographic medium and traditional photographic materials in processes that deviate from tradition. The resulting imagery is displayed, installed, or otherwise exhibited in an academic venue—an environment that encourages deviation, experimentation, and supports both successes and failures as integral aspects of process.

Bennie Flores Ansell deconstructs the tools of analog photography to create organic installations and unique objects. She achieves different effects through the reaction of varying light sources with reflections and mirrors, constructing distinct installations by configuring obsolete photographic materials as an ode to the photographic process.

At the outset of color film, the chemicals necessary to bring out reddish, brown, and yellow tones in the exposure were omitted, giving film photography an inherent racial bias toward white as an “ideal” skin tone. It was not until the 70’s and 80’s that the lack of necessary chemicals were challenged, and only then by advertisers who were unable to capture and accurately market products such as wood grain furniture and types of chocolate. It was these challenges that finally spurred companies like Kodak to change the chemistry of their color film to include these tones.

Flores Ansell began experimenting with film sprockets as a way to pay homage to the process of film moving through a camera. These perforations have existed as a structural part of the film roll almost since the beginning of photography— a simple, fundamental construction to move an image forward. Before color truth, however, this movement left many behind.

By removing these film sprockets from their accompanying images, they take on an intrigue all their own, free from the substantive elements that once made them discriminatory. Flores Ansell has threaded these sprockets into a single corded structure to create overlapping strands of time. These timeline strands give deference to the history of the artform: the ages of film, the evolution of the process, and the shift in photography. Sprockets from the 50’s are adjacent to ones from the 70’s, evoking the nonlinear characteristics of time as both a process and a story. These sprockets, as objects in time, amass to bring these histories to life.

As a byproduct of cutting the sprockets, Flores Ansell’s work subsequently creates a dialog between Analog and Digital by using the imagery from discarded Art slide libraries. She condenses images from slide film into sliced and gathered 1– inch dots, which viewed at a distance, show only color and shape, but when viewed closely reveal the original images that are still present. The swarms of dots constitute the reverse (or opposite) of pixilation. Digital language occurs in dots per inch, or dpi in digital printing. 1 dpi is now the one-inch analog shape casting its shadow and becoming light. Flores Ansell uses mirrors in installations to enhance the shadows and project light.

bradly brown

As the separation between our physical and digital surroundings becomes increasingly blurred, and we must continually re-engineer the boundaries of the artistic medium. Imperative to my practice, photography is a tool which allows the work to begin as experiential and expand into the cerebral due to its ability to bridge the gap between documentation and expression.

Blending drawing and painting with the process of photography has led to a series of digitally produced renderings that reassess the tools and techniques from photographic history. In both Trees, and Webs, the computer monitor becomes my camera lucida, as every detail of a photograph is interpreted by my hand using a stylus and trackpad.

Each leaf of a tree is identified, each strand of the web is recognized while staying true to the original photograph. After rendering the drawing, the output of the digital image onto a physical material challenges the idea of the sacred object. The torn sketch book paper or the frayed edges of the canvas, imbue the work with uniqueness, yet the image itself is infinitely reproducible. Similar to the cliché verre, these pieces question how the art object is valued; what is the worth of a physical object as compared to the digital information that defines it?

amy theiss giese

ski a gram n. [Gk skiashadow + -gram from Gk –gramma, from comb. form of grammasomething written or drawn]

Enter the room. Captured light, both its absence and excess, is arrested, hanging on the wall. There is a compression of time and space encapsulated in these impressions that references the constant, ongoing emergence of the past, which can never fully materialize. Shadows are stilled, seized, lost. Scrolls of paper in varying lengths hang from the walls. The shifting shades of gray move across the surface. Patterns repeat, shapes emerge then recede, sometimes revealing their referent, other times remaining elusive. Embedded in each scroll is an abstracted compression of an experience, yet they also simultaneously hold the direct reference to the actual space and time—light written, recorded, captured by an alchemical process.

Sounds emerge, beginning faintly then building, moments where it all seems recognizable, then the tones shift, drift and they move away. The sounds of a space, in a space expand over time, the time that relates to the original experience, the time referenced in the shadows. Awareness develops that there is a correlation between what is seen and what is heard. The experience, taken as a whole sits just at the edge of abstraction, asking the viewer to question what they see, what they hear, and how they relate to one another.

Exploiting the indexical nature that is inherent to photography, I am presenting the viewer with a collapsed moment of reality, a trace in two dimensions of something that once was a full corporeal experience. The shadow left on the paper is an abstraction of a moment, a translation of it. The large-scale, unique, silver gelatin skiagrams that I make are a direct recording of the shadow patterns in a room at night. No camera. No lens. No aperture. The referents that ground us in our own visual world are removed, and you are left with indistinct yet indexical images, actual visual abstractions of a space. The aural projections are an additional abstraction of the original experience and also a translation of the image itself via the constructed space of digital software. Shifting grains of silver to pixels then to MIDI notes to reinterpret that original impression.

The play between the projected sound with its linear progression of time with its physical presence in space and the implied time inherent in the flat representation of the skiagram sets up a juxtaposition that challenges our experience of both media and their relationship to one another and to reality. And it is in the translation, both visually and aurally, that I hope to create a parallel space that a viewer can walk into, making them question what they see and how we perceive our surroundings.

andy mattern

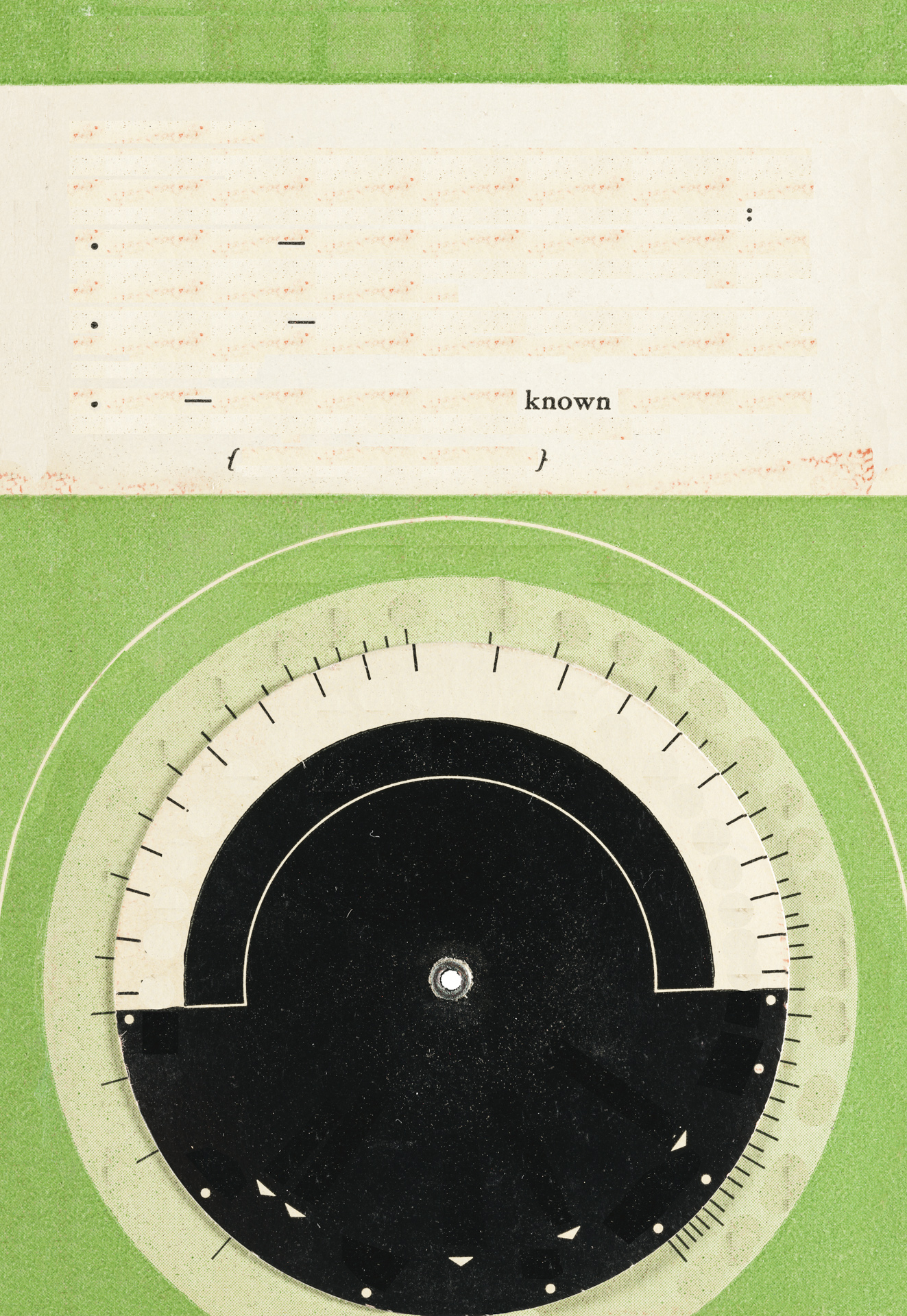

Turning the camera on its own logic, the photographs in Average Subject / Medium Distance reconfigure paper guides once used to determine exposure and other image settings. Stripped of example imagery, technical numbers, and explanatory text, these relics from mid- century photographic practice are reduced to their underlying structure. In the process of removing this information, digital traces are created, shifting the surface into a rupture between physical and virtual, analog and digital, functional and useless.

This process creates a new surface that hints at formal mandates in the medium. A single word remains in each composition in its original location, while all other information has been neutralized. This word operates as a springboard for interpretation while pointing to the priorities and conventions conveyed by the original object.

A chemigramist and photographer for over forty years, Nolan Preece has devoted his work to understanding and mastering the challenging techniques of early photography and conceiving of new photo-based processes at the same time. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, his fondness for experimental photography led him to originate a photographic abstraction process that employed chemical masking techniques and staining in conjunction with a printed image. Preece called his resulting prints“chemograms,”but after recently engaging with a group of artists using similar processes—most notably Pierre Cordier of Brussels, Belgium—Preece has taken to using the term “chemigram” to describe his prints. Chemical graphic structures and coloration play an important role in much of this work by providing a visual uniqueness for environmental themes.

Preece’s interest in nature has always been a constant, from growing up in the desert, to being a river guide in Grand Canyon, to working as a field photographer for environmental impact statements in the 1980s, to creating an on-going series of landscape photographs and chemigrams. Douglas Collins with the Manhattan Graphics Center has summed up his work in an article he recently wrote. “Somehow - you have to stare at these pictures for awhile for the sensation to grip you, but it will - he manages to draw the viewer into a ragged, moon-struck environment at a level that is close to the ground; we feel the way a small breathing creature must feel, a bird darting in the brush, a small snake, a muskrat, though none are seen; it is a world under our eye but totally alien to our species, devoid of humans. In this way it becomes uncanny, and this in turn is responsible for its strangely compelling hold on us. We should get used to it he seems to be saying. How does he do this? By his choice of colors for one thing: inverting what we expect in a representation of nature. There are no angels here. It is a primeval scene that could go either way. Nothing stirs. It awaits our signal, our consent, perhaps our involvement. In the years I’ve been following him it has only been with this work that his twin passions, darkroom tinkering and recognizing our stewardship of the earth, have come together in an unapologetic fusion that is of the most potent art.”

Preece experiments with everyday materials such as acrylic floor wax and common photographic chemical solutions and papers to produce his images. He often moves beyond the one-of-a-kind chemigram print by employing digital manipulation. Belgian photographer Pierre Cordier, who is widely respected as the founder of the chemigram field, referred to Preece in 2012 as “without a doubt, one of the outstanding practitioners of the chemigram.” After meeting Cordier, Preece was inspired to invent the use of acrylics and other substances as resists, beginning a very productive phase in his art and he has continued to create images of surprising complexity and beauty, exploring new methods. In 2016, Cordier endorsed him as a pioneer in the chemigram field by stating “You work like a painter who controls the forms of his work but you use masterfully the chemigram technique to make images that no one has seen before.”

A special thanks to the Nevada Museum of Art for contributing to this essay.